|

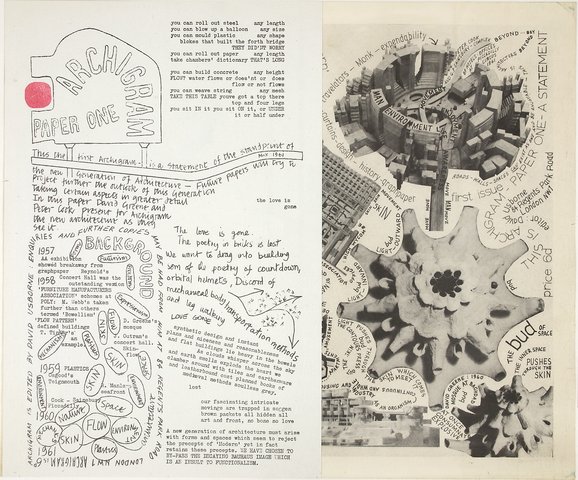

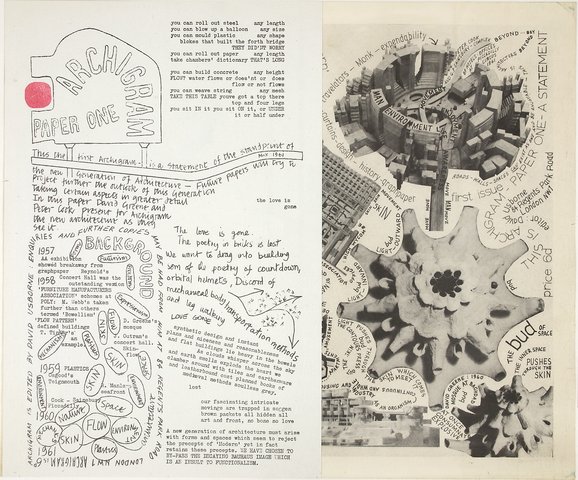

| Cover in Archigram No. 1 (1961) |

The love is gone.

The poetry in brick is lost.

We want to drag into building some of the poetry of

countdown, orbital helmets.

discord of mechanical body transportation methods

and leg walking

Love gone.

Lost

our fascinating intricate

movings are trapped in soggen

brown packets all hidden all

art and front, no bone no love.

A new generation of architecture must arise

with forms and spaces which seems to reject

the precepts of 'Modern' yet in fact

retains these precepts. WE HAVE CHOSEN TO

BYPASS THE DECAYING BAUHAUS IMAGE

WHICH IS AN INSULT TO FUNCTIONALISM.

You can roll out steel any length

You can blow up a balloon any size

You can mould plastic any shape

blokes that built the forth bridge

THEY DIDN'T WORRY

You can roll out paper any length

take Cambers' dictionary THAT'S LONG

You can build concrete any height

FLOW? water flows or doesn't or does

flow or not flows

YOU CAN WEAVE STRING any mesh

TAKE THIS TABLE you've got a top there

top and four legs

you can sit IN it you sit ON it, UNDER it or half under

A poem in Archigram 1 by David Greene.